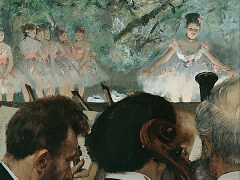

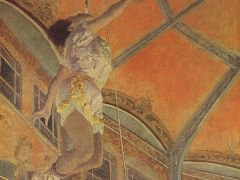

Two Dances on Stage by Edgar Degas

Ballet, relative to other art forms, was an anomaly in Degas' time. When new artistic movements were gathering steam - Impressionism, realism, and romanticism at the forefront of the parade of isms - French ballet remained a bastion of classicism. Precision, poise, technical proficiency. These were the objectives of a French dancer. The body never out of position, the classical line held both figuratively and literally, the limbs always in alignment with fingers, feet, and head. In spite of its near-regimental formality, the classical method had a sort of alchemy to it - a way in which strict adherence to technique transformed craft into art. Classical purity faithfully fulfilled that one requirement of good art that seemed so elusive - true understanding of the art form. Virtuosity meant connecting with and personifying the art's essence, becoming its ideal. Coldly classical, and yet innately balletic.

But Degas operated in realism. There are hints of classical rigor here and there. A visible relic of a grid pattern and the fact that each dancer en battement is in exactly the same position indicates the use of studies and in-depth preparation before oil was applied to canvas. Indeed, Degas would often sketch drawings from life or photographs, transfer the images onto the canvas, and then modify them to comport with the work as a whole. In some cases, the last step was repeated several times as Degas scraped off parts of a painting and redid them, adding new characters or changing the setting. Meticulous craftsmanship is where the similarity with classicism stops, however, as Degas stuck to the realist credo of depicting life as it is without photographic accuracy. The lighting of the room is masterfully exact, the combination of dull palette and natural light from the windows providing the muted glamour of a ballet rehearsal. The dancers' extremities are vague. Fingers are gnarled if at all visible. Faces of the dancers in the foreground are lightly sketched, but most have no face at all. Their limbs, the cradle of the arm where the elbow is slightly bent, the curve of the calf visible below the tutu, are delineated with special clarity. It is no accident that classical ballet also emphasizes these parts of the body. The one extremity that Degas has chosen to detail is the dancer's foot, recognized by most as ballet's trademark. The dancers en battement are given point shoes with little to no shadowing, indicating the foot is perfectly balanced within the shoe; the raised foot exhibits a perfect dancer's point. Contrast that to the dancer at the barre, whose left foot is slightly leaning to the right while her leg stays straight, indicating imperfect balance. The slight curve of the shoe underneath the foot's arch owes to the stiff shank supporting the dancer when she is en pointe. In the painting, the feet are as alive, if not more so, than the limbs.